At 8,611m, K2 is the second highest mountain in the world, but the most difficult mountain above 8,000m. It’s a mountain that no climber has reached the peak of in winter. This was a major challenge for many experienced climbers. Seven Summit Treks decided to organise a mission to try the mountain, and I had the honour and pleasure of also being invited, as the only Greek. The truth is that the chance of success was estimated at about 3%. I couldn’t turn it down and not try. I thought that if I didn’t go, it would torture me for the rest of my life that I hadn’t tried, that I hadn't gone there.

And so, on December 20th, we met up in Islamabad in Pakistan, nineteen climbers from seventeen countries, and we arrived in Khartoum on an internal flight. From there, we began a trek through the Baltoro glacier, which was 120km, until we reached the base camp at 4,970m on December 26th.

I saw K2, and that first image provoked a sense of shock and awe, and, at the same time, the feeling that we would never conquer the mountain. It might conquer us. And the only thing we wanted was for it to allow us to reach its peak, to visit it, to pay our respects, and then leave immediately.

It was a hard winter, so we were forced to spend the night and be there in temperatures from 19 to 29 below zero for the whole twenty-four hours. What we all had to do was to begin to climb gradually. This is the process of rotation, or acclimatisation. And we had to spend about six to eight nights over 6,000m.

The cold caused dehydration, so you had to constantly drink water. And it caused great tiredness and exhaustion. Under these circumstances and seeing this, it is logical to think: “What am I doing here? Am I normal? Why am I doing all this? Why am I here?” I remember, I opened my sleeping bag, and inside a bag, I found one of my eight-months-old granddaughter’s onesies and a message that said: “Granddad, when you come back, I’ll have learned how to hug. So, I’m waiting for you with the smallest hug in the world.” But, on the other hand, you have that feeling that you need to get to the peak. I knew why I was there, and I could deal with the rest. And that’s why I could beat, if you like, the other part of me, the other voice that kept saying: “Go back to your normal life.” And I stayed there, amid everything I wanted so much.

January 16th, the day that ten Sherpas managed to write their ascent into the world history of climbing in gold letters. They were amazing. They managed to get to the peak. They found a window in the weather and succeeded. The same day, during my descent from Camp 1 to base camp, I stopped on a plateau at the Japanese camp to phone my son to ask if the Sherpas had arrived, because I know that they had left for the peak in the morning.

At the very moment I was speaking to him, I heard a noise. And then I saw some objects falling. I say a body sliding down with unbelievable force and speed. And I shouted: “Ahhhh! He’s a goner, he’s goner, he’s a goner! It’s Matia! It’s Matia!” I called on the walkie-talkie to the head of the mission and I told him what had happened. He said: “Calm down. Get down there quickly and see exactly what has happened and who it is.” As I was heading down, I heard on another radio that it was not Matia but Sergi, the Spaniard, the leader .

It took me about 15 minutes to reach him. He was just barely breathing, but he had serious injuries. The rest of his body was inside his snowsuit, curled up. He seemed to have some serious fractures.

We immediately tried to get a helicopter from the Pakistani Army, because only they can fly there. But it wasn’t coming, they said it would be the next day. And shortly after, while we were all standing over Sergi again, we realised that he had stopped breathing and had died.

That shocked us, obviously. There were about six of us there. They were very emotional moments. We held each other. We all cried together.

There was stunned silence for at least twenty-four hours the following day. The place where he used to sit was empty. And, of course, there was discussion about whether we should go on. When you see such an experienced man—the head of the mission—die, it is more than logical that you think about what could happen to you and that what you had worried could happen, happened. So, it could happen again, and death could strike again.

In reality, what I usually think is exactly that: that it couldn’t happen to me. Too much optimism? The feeling of experience that makes you confident, and you’re sure that you’ll avoid mistakes? The reason behind it is your passion for achieving both the mountain and your aim, and that you mustn’t quit because this has happened: because now you want to do the climb for him, as well, and dedicate the peak to him. That became the intention behind everyone continuing the mission.

From that day on—January 17th—we looked for a window in the weather to begin the final effort, to try for the peak. Long story short, we saw a window which appeared to open on the 4th and 5th of February, and we decided we would begin our final attempt on February 2nd.

We set out, the fourteen of us who were left of the eighteen, because Sergi had died and three others had withdrawn. Fourteen of us and three from the other team. And, indeed, the fourteen of us reached Camp 1. Five out of our fourteen decided to go back on their own and not continue. The nine of us continued to Camp 2 through extremely difficult conditions.

I was carrying everything with me: sleeping bag, gas canisters, lots of things. My load was really quite heavy. I called my son and told him that I was really tired. “It’s the first time I feel so tired. How can I get through it? I really want to reach the peak. I’m going to have to find the strength to continue.” And then, he said something that really gave me unbelievable strength and the boost I needed: “You’re the oldest there. You are the most experienced. You can do it. Just remember that, at this moment, thousands of people in Greece are watching you.” I was really moved, even now as I’m telling you. It’s incredible to hear a message like that from your child and know that all of Greece is watching you. That, “all of Greece is watching you” was magic. It really did lift everything I’d been feeling from my shoulders.

When we reached Camp 3, night had fallen. It was 8.30 in the evening. It was really cold. I didn’t have a thermometer, but the forecast was for 39-41 below zero. And then, unfortunately, we discovered that no tents had been left for us to put up. We had expected the Sherpas to have left them from the previous time. We looked in the snow to see if we could find them. But we didn’t find anything. Time passed. I remained in that temperature for about fifty minutes without moving, which resulted in me feeling pain in my legs. Especially in my toes, very intensely. And because I know what frostbite is like, I realised that frostbite had begun to set in.

There were seven or eight of us in each tent, while the tents were intended for two, three at most. I took off my shoes. I was trying to see what was going on, to find out what was happening with my feet, and the German said to me: “Your feet are in a bad way. You shouldn’t go on because you’ll have a serious problem.” I knew that, too; I understood. But I tried to massage my feet, to see I could resuscitate them, put on other socks and continue. No one else wanted to continue due to the extreme cold. Of course, I really wanted to go on.

It was beyond doubt that if I went on, regardless of what happened on the way, I would have a serious problem with my feet. “Serious” could mean even having my toes amputated. It might not mean that, but what was sure to happen was that it would keep me from the next mountains and the plan I had to climb all fourteen peaks over eight thousand metres. So, this thought— that I couldn’t do this—forced me to not continue for the peak.

The four—the two other Pakistanis, the Icelander, and Juan Pablo from Chile—who left for the peak, never came back. The rest of us didn’t continue and are still alive today. That is what happened and all we know it. As regards there being any bitterness or regret, or if today there is still a desire for the peak or any second thoughts, the fact that I’m here today and talking to you proves it was the right decision.

The way down was equally difficult, equally dangerous, and more so because we had no food and had not drunk anything since the previous night. The danger that you could make the slightest mistake was always there lurking in the background. So, I was incredibly careful. At the moment, when everything was going on, and I was thinking and doing, I heard a Sherpa further down—the Sherpa with Atanas from Bulgaria—shouting: “Antonio!” “Antonio!” Tragically, he was gone; he was killed.

I will always remember our five companions who were lost, for their bravery, their self-denial in trying to reach the peak, their state of mind, the greatness of their spirit, and for yet another important lesson that, when you are really passionate about something, you might ultimately have to sacrifice yourself for it.

I felt so good when I saw my family. I felt all the care and warmth I had been missing all that time. As well as the joy of being alive, because it’s a tragedy for them to bring you back in a box. You don’t have the right to do that to others. You shouldn’t cause grief for those who love you.

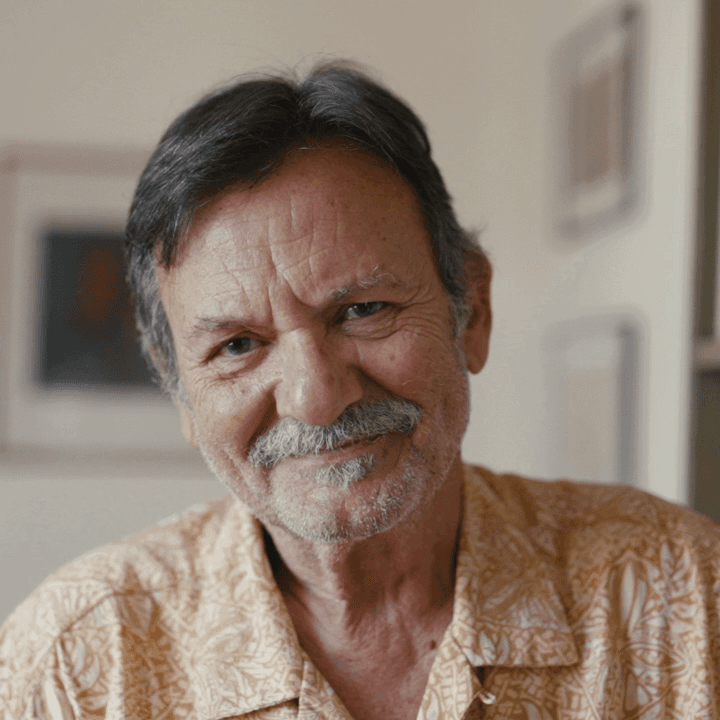

I’d said from the start that my desire to reach the peak definitely came from personal motivation, from a personal ambition and a goal. You can’t do these things without that. You are motivated first and foremost by this, your own ambition, your own vanity, if you like. I really wanted to climb—I haven’t said this before and never really felt the need to—for the Greeks, for Greek mountaineering, and less so for me. It was this that took hold of me to the extent that I forgot that I’m obliged to come back alive, not to cause those I love unspeakable grief for the rest of their lives by losing mine.

I understand that through my efforts I have encouraged many people to succeed in the goals and dreams they have set for their lives. It is so impressive when someone writes to me and says: “I beat cancer watching your efforts and believing that anything is possible.” Another said: “My baby will be born on Monday, and the first thing I will tell him when he comes into this world is your story.” And I understand that, ultimately, all this, leaving aside my own madness—let me put it like that—has a benefit, because it can encourage these efforts in other people.