A RIDE OF DISCOVERY

A RIDE OF DISCOVERY

Description

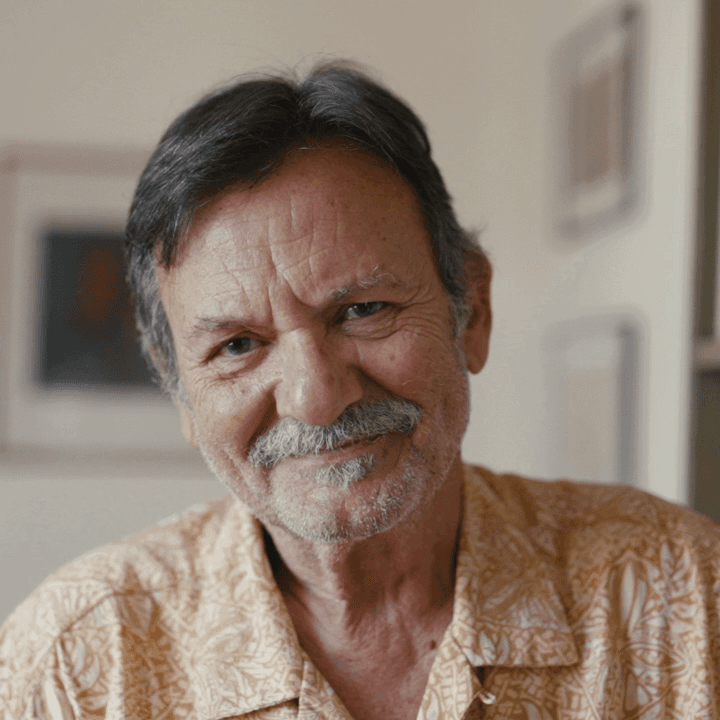

Vassilis Messitidis is the only Greek to have crossed four continents on two wheels.

Tags

Credits

Field Reporter

- Kwsths Kotswnhs

Interviewee

- Basilhs Mesitidhs

Podcast Producer

- Xaris Pagwnidou

- Magia Filippopoulou

Sound Designer

- Iasonas THeofanou

- Dhmhtrhs Palaiogiannhs

Sound Editor

- Dhmhtrhs Papadakhs

Voiceover

- Nicholas Seymour Stathopoulos

You know how they say that many things in life are just a matter of luck? Well, this was completely luck. And when I say ‘completely’, I mean completely.

In 2005, I remember going into a bookshop and catching sight of a book about two French cyclists who had cycled around the world. When I saw it, a light bulb went off in my head. Very simply, I said, ‘Think about this a second. You want to do something; you want to travel. And you still haven’t found a way. Here’s an idea!’ And just like that, I started to look for a bike to make my dream come true.

I prepared for three-four months – about that long – from the beginning of the year. I took maps from a plain atlas. We didn’t have mobiles then like we do now, everything easy, with Google Maps. Not even the internet was as common as it is today, not even close. Simple maps. On these, I drew a route along the main roads, the main arterials, in each country.

I set out in May. Getting on the bike and leaving home, I cried; the truth is that I remember that. I started pedalling – it was a heavy bike, a solid 60 kilos – and with the wind blowing in my face, I felt free... I remember that. I found the feeling really beautiful.

I headed up to Derveni. In other words, I went through Thessaloniki, Egnatia, if I remember correctly, and on the second day, I reached Alexandroupoli.

Everywhere I stopped in Turkey, I remember people would come up to me, ‘Come and have tea. Come and rest. Sit down...’. And, of course, they asked, ‘Where are you from? What are you doing?’ ‘Dünya tur!’ ‘Going round the world on a bike’. They treated us like... like neighbours, like brothers. Whenever we asked for somewhere to stay in Turkey, ‘Can we sleep here?’ ‘Can we pitch our tents here?’, etc., we saw a huge difference between when a Dutch person, for example, or another foreigner went to ask and when we went, letting them know we were Greeks.

I did a section of the Black Sea coast and then headed to the border with Iran, Ararat. For me, Iran is a country that has stayed in my heart. If some people keep track of how many Airbnbs they have stayed in on their travels, I keep track of how many people’s homes I stayed in when in Iran. It was the country where, if I held up a sign which said, ‘Hospitality, hospitality, hospitality, hospitality’, I think Iran would win the world championship in that race. I was not used to people coming up and begging, ‘Please come. It will be a great honour for you to come and sleep in my home’.

It’s a country that has a lot of problems, closed off, and obviously has issues with human rights, but the people inside that... Let’s say ‘confinement’, are very open and hospitable. Obviously, I’m a man not a woman, right? Things are a little different between the sexes. But I had an amazingly positive experience. I crossed a country, and I was... I was flying high!

I left Greece in May, but the end of June beginning of July in areas of southern Iran, Pakistan, and India have heatwaves then; something I was unaware of. You are exposed every day, all day, to temperatures of over forty degrees Celsius, and, if I remember rightly, at some point – the thermometer was in the sun, OK? – even forty-eight when crossing the desert. There’s a lot of desert in the world.

In Pakistan, there was an area, rather underdeveloped, where, for a distance of six hundred kilometres, there was nothing for stretches of 150 kilometres. There, when my water ran out, I was forced to drink from large pots, which is where there was water. I drank water that was brown in colour. Unfortunately, this upset my system, and I began throwing up. So, after one, two, or three days of this, my body somewhat gave up.

I went six hundred kilometres by train to go to a main city where I got medical help. And, in fact I was hospitalised, and put on a drip for two days, until I began to get my strength back.

I caught a train to a city that I reached after many difficult kilometres, Lahore, which is close to the Indian border, where I asked for medical help. And I was hospitalised and put on a drip, for two days. My weight had dropped to fifty-seven kilos.

As soon as I got off the train, with great difficulty, my mind a blur, I remember there were steps. To carry up the bike, I had to take off my things. It took me two or three trips. It was like a marathon… it seemed like a marathon to me. To climb what? Twenty short steps. Although I had already covered five thousand kilometres. Five or six. Those twenty steps seemed harder than the six thousand kilometres I had already done.

Luckily, as I crossed into India, the temperature fell, because we were going into monsoon season, and it started to rain a little. I cooled off and, bit by bit, I got my strength back and got on with this beautiful journey. From then on, all the countries, from Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia to Singapore, I can say that, at that time, they seemed to me to be virgin territory.

I remember I had difficulties. It was the rainy season, and I had problems in Vietnam finding somewhere to camp, to put up my small tent. Because paddy fields were built to the left and right of the road... So, I might find myself camping in front of someone’s house, door, or the gate to his yard. And when they woke up in the morning and passed by, they greeted me, and I went on. I remember that I stayed in quite a few petrol stations in those countries. They had really good petrol stations. There was water and toilets; they were a life saver. We met people there as well, and talked about whatever we could communicate; obviously, they didn’t all speak English. The people were very different, simple, pleasant, with few possessions – like most of the world, obviously except for the western countries, where we are hung up on possessions and things – they were more relaxed, more peaceful. I flew from there to Australia, to continue into the chaos of the desert.

I got off the plane all well and good and waited for my bike, so I could continue my journey. And what happened? They told me, ‘Ah yes. Sorry, your bike will have to be quarantined’. What does that even mean? I wandered the city at a loose end, trying to find out what was going on, when they would release my bike, do the checks they needed to, and return it to me, so that I could continue my journey.

While I was walking through the city, by chance – and sometimes it is just luck – I saw a Greek church. And I went to inquire. They spoke to me in Greek! Where? In north Australia, in the middle of nowhere, and I just happened to find Greek people and indeed people who put me up in their home. I learned that, at the time, Darwin had ten thousand Kalymnians: Kalymnos had moved to north Australia.

I can say that crossing Australia was the greatest psychological challenge. Because the few cyclists I passed, no one was going in the same direction as me; they were going in the opposite direction. This was because, they told me and I learned for myself, the air masses have a constant course, at least during the time I was crossing. Every day, the wind was against me. In fact, the wind was my worst enemy. To avoid the wind, I noticed that it dropped at night. So, I cycled quite a lot of nights rather than days. I rested during the day and cycled at night when the wind fell somewhat.

Truth be told, New Zealand is a beautiful country, and I met some Maori. At some point, I had gone into somewhere to get a hot tea, and they came up to me and spoke to me. As soon as they heard that I was Greek, they took me to a wall, which was a monument to the locals, the Maori, who had gone to fight in the Battle of Crete. It was then I realised what a small world it is. You see, the Maori are Polynesian, and their facial characteristics and bodies are different to ours. Despite this, these people went to Greece, and you realise that they crossed the whole world to help our country liberate itself from the Germans, then, during the war. I found it amazing, right? I mean, just as you’re saying to yourself, ‘I’m a foreigner, and I have nothing in common with these people’, right then, you find you have something in common.

I didn’t cycle much in Canada, I started to go downhill because winter was approaching. The truth is that, in the western countries in general, people are more reserved, they have their own daily routines and are more self-contained. It is clear that the western world is not so interested in the people visiting their country.

I remember at Penn Station in New York, in Manhattan, I slept next to homeless people. I had somewhere to stay there, but I happened to arrive at 2 in the morning. Instead of looking for somewhere else and accommodation, I said, ‘I’ll go to the station, I’ll sleep there, I’ll put...’. I found some people sleeping somewhere nearby, and I lay down with my bike. Of course, at some point, the police came along and got us all up, ‘You’re not allowed to sleep here’, but OK.

Sleeping, when you are on a long journey... Finding somewhere to sleep is a whole process. Generally, you look for somewhere suitable. Sometimes it doesn’t work out, so you sleep wherever you can. Some of the places that have stayed with me: Iran. Sleeping under bridges; sleeping in the afternoon, to rest from that relentless heat. Imagine, the only shade you can find in a massive desert is under road bridges, with the road going overhead. Number one.

Number two. I remember a wonderful scene in a windstorm. So you understand, I was leaning to hold on to my bike, to be able to cycle. I was leaning at a sharp angle, which means the wind was really strong. I was forced to say, ‘I’m going to stop wherever I can find’. I found a building, like a small warehouse, open on all sides. There were no windows or anything, and it was full of rubbish. So, I used my feet a little to push the rubbish aside. I laid out my blanket and put my mat on top, and slept there, to keep out of all that wind, which really hurt when the sand hit you.

I remember being high up in Chile, where they have the observatory, where the sky is really clear, sleeping in the middle of nowhere, putting my blanket down again on the slope, without a tent, without a flysheet, gazing at the stars. That was fantastic; it has stayed with me. I have slept in so many places where you would say, ‘No one can sleep there’.

In Mexico, Guatamala, and all those small countries as far as Panama, obviously you see the high fences of the rich and then the shacks, the simple shelters where the rest live, most of the little people. But they are all cheerful, all really pleasant. I’m not saying there are no problems. There are problems everywhere, in all countries, but I can’t say that poverty means degradation. What impressed me is that it was easier for a poor person to give something than for someone who had everything. So, yes, I experienced, met, and tried to spend time with people who had less than me, but they gave more than I was used to giving.

One of the few times I felt slightly threatened was at a football match in Lima, Peru. At some moment, I saw some people in the distance. A crowd of them. By good luck, a young guy came up behind me, also with a bike, and he said, ‘As you are, turn around. Now!’ Before I could work out what was happening, I did what he said, and followed him. And, when I turned my head to look back, they were freaking out the passers-by, taking their wallets, their money, etc. And he says to me, ‘This happens a lot’. Generally, I had never been afraid before, there, I was a little. I was shocked, to put it simply. I was lucky that people didn’t see me as having money, a weary man with simple clothes, with bags, with things that didn’t seem worth much, weren’t shiny... weren’t, weren’t, weren’t... a muddy bike, etc. I wasn’t exactly looking fresh.

When you don’t know, you don’t fear. In Pakistan, I waved at some Jeeps, which I saw had massive guns on top, ‘Hi guys! Hi guys! Hi guys!’ Eventually, I learned that at the borders of Iran-Afghanistan-Pakistan there is an insane traffic in drugs, opium. And, obviously, this is all guarded. And these people, obviously, are not going to be bothered by a guy on a bike. I waved, and they waved back.

I had begun to get into the ‘almost there’ mood towards the end. The tour of Europe was like, ‘OK, I’ll do this and go home’. I had lots of experience of fire fighters. For some reason, the fire stations there were very organised, professional, so there was space, and I often stayed with fire fighters. In fact, in one station, I told them which city I was going to, and they said to me, ‘Ah, you should go and find these guys’. I slept there, they gave me food, I mean we ate together, and the next day, I went on my way to the next town, the next fire station.

From there on in, I did everything quickly. From the moment I set foot in continental Europe, France, Switzerland, Austria, etc., I shot back to Italy and Greece, until I finished. I ended this wonderful journey, which took fourteen months, with a tour of Greece. The finishing line was my home, where my relatives and friends were waiting for me, which was very moving at the end.

Fourteen months. I had set a budget and kept to that budget, about ten thousand euro, in 2005. Half of it, not to say more than that, was transport: aeroplanes, air tickets, boats, etc. Just financially, it was cheaper than if I had spent those months in my country.

Having done that long journey and much more, you come to understand that you are insignificant and you need to pull yourself together a little. We don’t have the control we think we have, and nor are we as important as we think you are. You learn to appreciate, you learn to respect diversity, and you learn to respect your home, and the home that is your greater home, the planet on which we live. I think this journey made me a little more human, like I would want to be.