I was born in Palaiokastro, Serres, in 1940. From my early childhood, eight years old, they took me to my first field; they took me in cart to pick cotton. They put me in an apron, and we bent over to pick. I learned to pick. Not that I was the best, but I was a baby, a young child.

When I had grown a little, I followed my father. He would say: ‘Koula’, he said, ‘do you want to come with me and go and see the first variety that we will plant? Or if the cotton has sprouted?’ ‘Yes, Father, I’m coming.’ We went together all over the plain, and I learned to love the land. I learned all the secrets of the land because my father was passionate about it. I kept asking: ‘What will you sow in this field, Father? When will it grow? Has it grown? Will we re-plant it?’ I had a child’s curiosity. I was young, but I was interested in the land. I adore it.

I went to school, and, during the breaks, I would sit under the acacia, the tree, when it was break time and all the children were playing. I would read my copy book, my spelling, to learn it, so that when I got home, I had already done my homework, and I could take my hoe and a little fresh water and go to the field to help my father.

From ‘50 - ‘55, all those who had a special field—it had to be sandy—were allowed to plant poppies. We had my grandfather’s lot, eleven stremmata, and we planted... Every year we planted eleven stremmata of poppies. The government itself allowed us. We even got the seed from the Agricultural Bank.

I went to dig with my hoe, just a young girl, and when I stood up... The field started high up and descended to the field further down. Eleven stremmata with all the colours: dark lilac, light lilac, yellow, white, light flaming red! What a wonderful thing... A field in bloom... I would sit, put my hoe over my shoulder, and admired it, I couldn’t get enough. And, when I was there, I went in between the rows, spread my arms, and touched the flowers. I kissed them, talked to them, they were so beautiful! I remember so clearly. We didn’t have a camera to take pictures.

When the poppies had grown, the leaves and all the petals fell. The husk dried out, the head, and we cut them. Firstly, we cut them with the stalk, about this long, so that we could hold them and then cut them with a knife. We tied a sack around our waists, and we threw them in there. When it was full, we emptied it onto a cart. We set up a canvas inside the cart so that they didn’t fall, because they were dry, fragile. Yes, the husk was closed, the head part, but, as it was dry, if you touched it with something sharp, it would open.

We gathered them, took them home, and spread them out under a plane tree in the yard on another large canvas. We cut the head with a knife and through them, nice and clean, onto the canvas or into a bucket, to put them in bags. And as we sat there, as children, and we took whichever colour we liked—they were grey-white inside, dark and light—I popped them into my mouth and ate them. I liked them, like sesame.

But the opium... I don’t know, it’s only after all these years I put it together... We used to sing a lot! Me, my brother, and my little sister, we sang whatever song came out. The whole neighbourhood could hear us, and, when we didn’t sing, we were tired, they would come with their sticks, banging on the door, and saying: ‘The neighbourhood larks aren’t singing, what’s wrong?’ I didn’t know that it was... It affected the body. But we ate a lot!

We gathered them and gave them to a man in Siderocastro who had an olive press; we gave him the seeds and he gave us oil. But he sold it, we didn’t know what, I don’t remember what Mr Alekos did with it, but we gave it to him.

During the Junta, the police came and said: ‘It is banned, you cannot grow opium!’ ‘Poppies’ is what we called it then, that’s what I knew, I didn’t know anything about ‘opium’. ‘Poppies are banned!’ My father said: ‘But that field is special, and I get my oil from there, I don’t get opium. I give it to what’s-his-name, at the olive press in Siderokastro, Mr Alekos and’—everyone knew him—’I get my oil. What will I plant there? Not sesame. Wheat grows too small’, because it was sandy. A gully crossed the field and when the rain came it would wash everything away. He said, ‘opium is all that we saved, and the crop is good because it flourishes there.’ The other said: ‘They are banned, do what you want. And these here, what are they?’ Farther down from the yard where we worked on them, the seeds fell into the garden and sprouted. I was there, and I said: ‘Why? Those are flowers’—I hadn’t known until then—’flowers, officer’. He said: ‘Those are not innocent flowers’, he said to me, ‘Do you know that they are a narcotic?’ I said: ‘What’s that?’ I had no idea until then; I hadn’t heard of it. ‘You don’t know’, he replied, ‘but your father does.’ ‘They are not innocent, they are prohibited, Gregory!’ And they cut them down and, from then on, it all stopped.

When I grew up, I thought, ‘That’s why we kept singing’, I thought. Why did we sing so much, like parrots, like larks? It must have been from the opium we consumed!

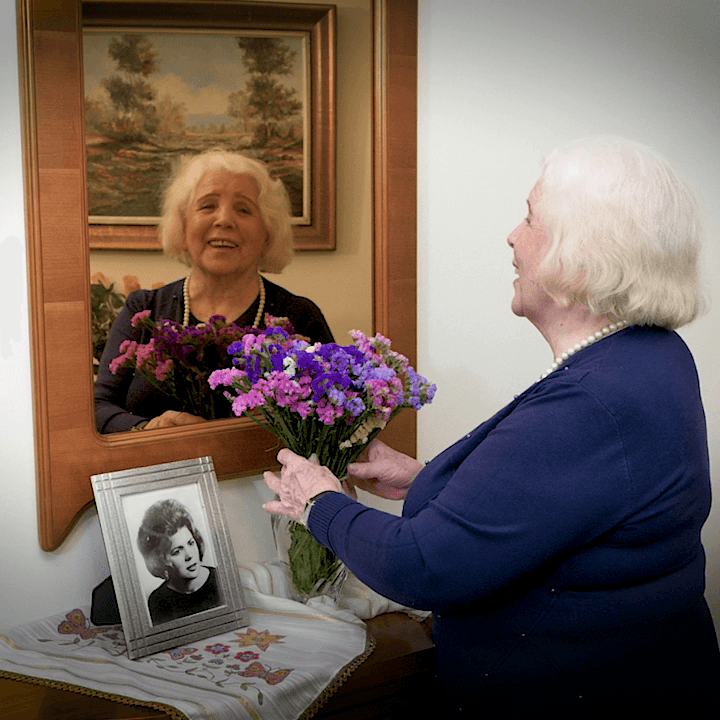

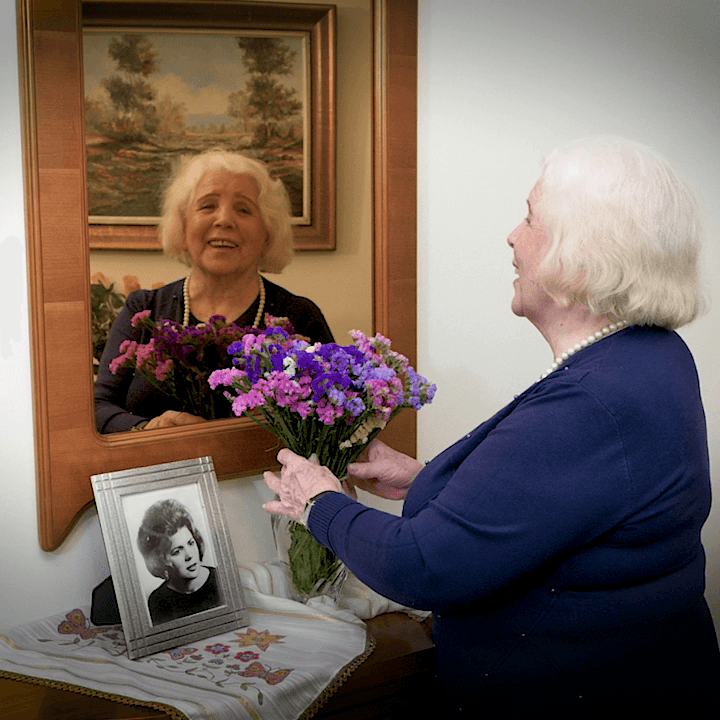

I hold onto it as something beautiful. An image... A rainbow of colours, beauty; I keep it and it’s like I’m seeing it now: I’m standing up high and I see eleven stremmata of colours, colours in bloom, so beautiful. I even saw it in my sleep, it was so beautiful, colours, colours... And you know, it was quite big, about this size, and I went among them, and I pushed my way through them... What joy, what joy!