Have you noticed how often in Greek history the Greeks say “no”? Istorima presents ten times the Greeks have refused.

1. THERMOPYLAE

In 480 BCE, a force of only seven thousand Greeks, led by King Leonidas of Sparta, held off 100,000 Persian forces for three days in the Battle of Thermopylae. While the Greeks were ultimately defeated, the Battle was decisive not just in Greek and Persian history, but also in shaping a fierce tradition of Greeks defending their soil at all and any cost. The word “Thermopylae” is now synonymous across the world with extraordinary resistance and bravery in the face of the most hopeless of challenges.

2. THE FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE

In March of 1449, the new Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI Palaeologus entered Constantinople to begin his reign. Surrounded by Ottoman territory on all sides, everyone knew it was only a matter of time before the City would fall. In early 1453, the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet amassed 150,000 troops and hundreds of ships around the City. On April 17th he delivered an ultimatum to Constantine: “Surrender, and no one will die. Resist us, and you will be destroyed.” Facing sure defeat, Constantine said “no”. That night the assault began and within six weeks the city fell, with all Greeks killed or enslaved. Constantine himself died in battle and his body was never found. Because of the dignity with which he refused the Turkish ultimatum, this most devastating battle – which led to 400 years of Tourkokratia or Turkish Rule– is remembered both as a tragedy and a source of religious hope and national pride.

3. THE MOVEMENT FOR GREEK INDEPENDENCE

In 1803, the women of the Villages of Souli, in the famous “Χορός του Ζαλόγγου,” or Dance of Zallogo, threw their babies off the cliffs and then leapt to their deaths rather than surrender to Ali Pasha, the Ottoman Governor whose capital was in Ioannina. This dramatic “no” became swiftly known throughout Europe, and the Paris Salon of 1827 featured romantic paintings of the event. Word of the Greeks’ bravery spread rapidly, and Western support for the Greek movement for independence grew. The refusal of the women of Souli inspired resistance of other sorts as well and set the Greeks rebels out on the course that determined Greece’s fate as an independent nation.

4. VENIZELOS IN WORLD WAR I

Eleftherios Venizelos, the most famous statesman of Modern Greek history, was a man who liked to say “no” and built his political career on the refusal to do what others wanted. Venizelos himself said that the contrary circumstances of his life were such that at a young age he “became a revolutionary by profession.” Of all his refusals to do what others wanted, the most complex came during World War I, when he rejected King Constantine’s insistence that Greece stay neutral. The King issued a warrant for his arrest, and the Greek Archbishop anathematized him, but in the end, Venizelos had his way – which in many ways set Greece firmly on its path to becoming a modern European nation. Venizelos is remembered today as Greece’s greatest leader. The greatness of his leadership was inextricably intertwined with his repeated refusals; and by his own account, his greatest political failure came at the one moment that he said “yes,” and signed the Treaty of Lausanne.

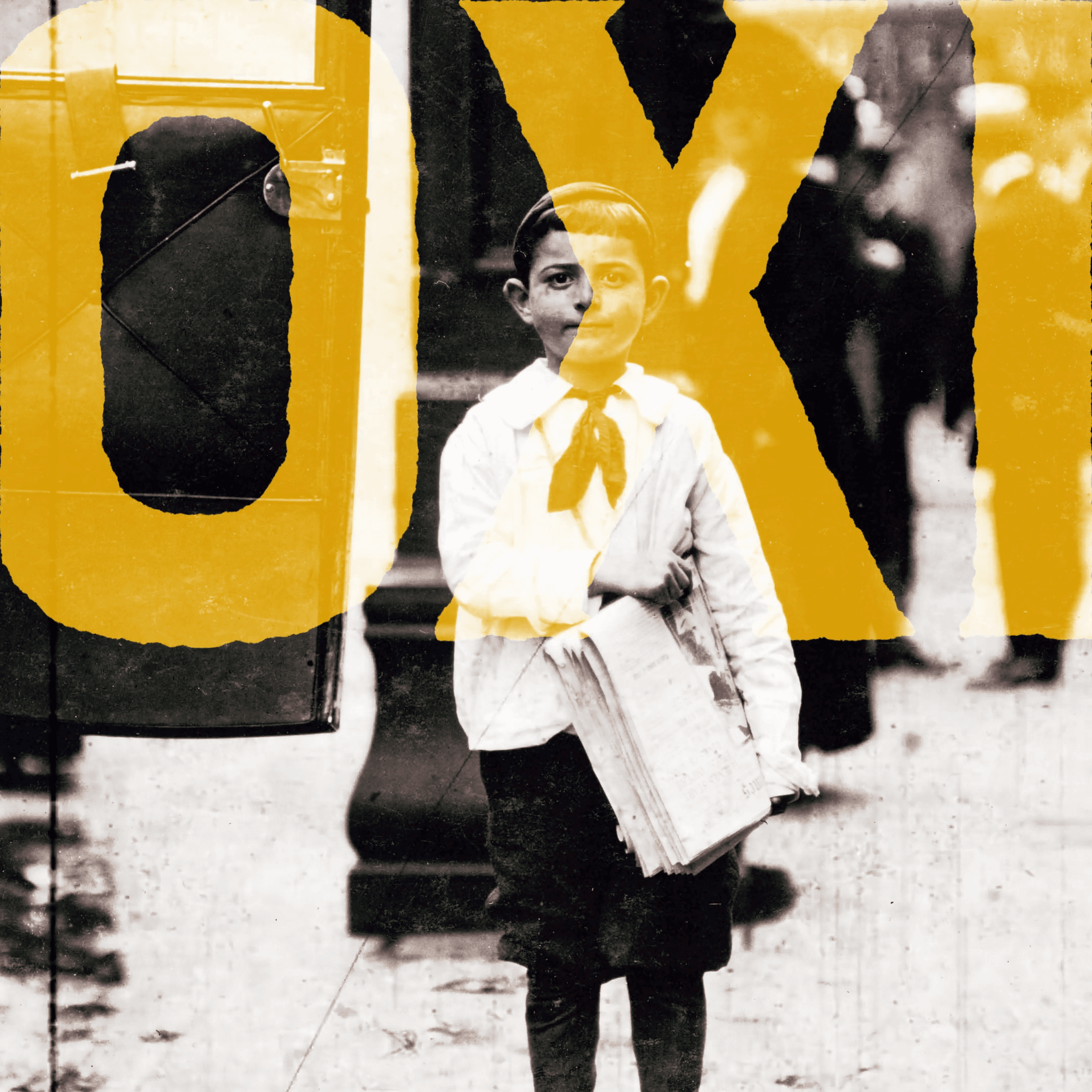

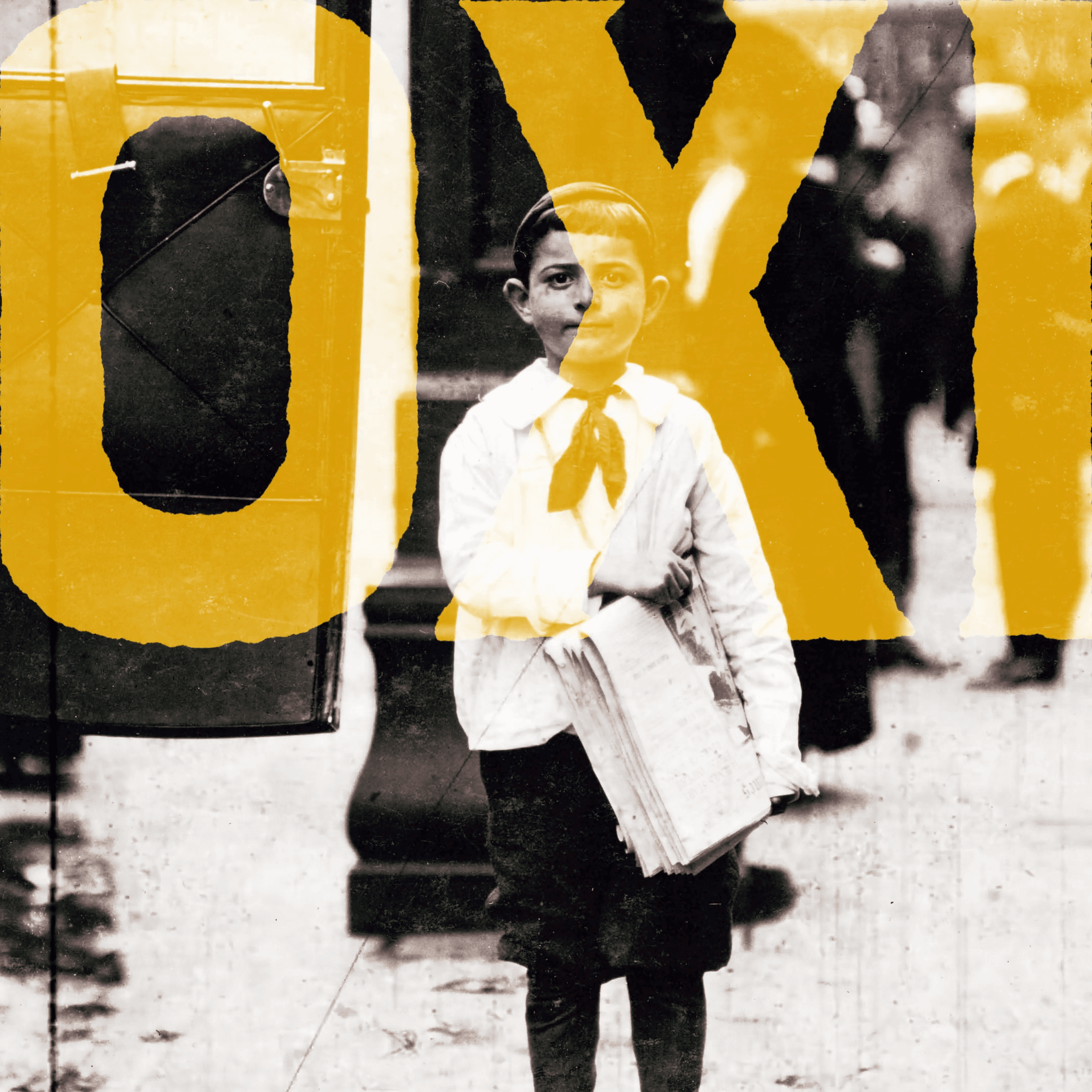

5. THE GRECO-ITALIAN WAR

On October 28, 1940, the Italians, whose troops had been hovering for months on Greece’s northern border, issued an ultimatum to Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas. If Greece wanted continued peace between Italy and Greece, Metaxas must allow Italian troops to cross the border and occupy Greek territory. With his famous “NO”, “OXI,” Metaxas refused, prompting a modern Thermopylae, one of the most valiant battles the Greeks have ever fought, as more than half a million Italian troops were held back at the Albanian front by a Greek army just a fraction of this size. And while ultimately Greece fell under Axis occupation, this battle set the tone for Greek resistance and bravery during the war – and beyond.

6. THE BATTLE OF CRETE

On May 21, 1941 the Germans launched “operation Mercury,” a massive airborne invasion of Crete. This began the famous Battle of Crete, in which the entire Cretan population rose up against the Germans. While at first outsiders dismissed the Greek fighters as “nothing more than malaria-ridden little chaps,” soon the Cretans emerged as fierce and brave fighters, old and young, male and female alike. The battle of Crete was historic in several ways: it was the first time the Germans used paratroopers en masse, and the first time the Allies made use of intelligence gathered from deciphering the Germans’ famous “Enigma code,” the secret code used in their military communications. But it has become most well known as a glowing instance of widespread civilian resistance to armed invasion.

7. ZAKYNTHOS SAVES ITS JEWS

The Holocaust destroyed the Jewish communities of Europe. In Greece, 87% of Greek Jews were exterminated – on a percentage basis, one of the highest decimation rates on the continent. But on the island of Zakynthos the story was quite different, because of a brave “no” uttered by two individuals. All of the island’s 275 Jews survived. When the Mayor Loukas Karrer was ordered – at gunpoint – to provide the occupying Germans with a list of all the island’s Jews, he and metropolitan bishop Hrysostomos turned over only two names: Hrysostomos and Karrer. If the Jews were to be deported, the Mayor and Bishop would be deported with them. This act of bravery bought enough time for the island’s Jews to be hidden with families across the island. To this day, there is a special bond between Zakynthos and the descendants of the Jews saved by the “no” spoken by Hrysostomas and Karrer.

8. GREEK STUDENTS SAY NO TO THE MILITARY DICTATORSHIP

The Greek military junta of 1967-1974 stands as one of the most painful periods in Greek history. And as with other moments in Greece’s history, it was a brave “no” from one of the weakest sectors of society that brought about historic change. The Athens Polytechnic uprising of 1973, in which unarmed students stood up to military power, led to the ultimate unraveling of the dictatorship. In turn, it led to other dramatic shifts in Greek politics and society, most notably in the abolishment of the monarchy in 1973 and the start of the Third Hellenic Republic a year later.

9. THE PLEBISCITES OF 1973 AND 1974: A “NO” TO THE MONARCHY AND A “YES” TO THE REPUBLIC

Since the first King of the Hellenes, Otto, arrived from Bavaria in 1832, Greece has had a tortured relationship with its Monarchs. Greece’s greatest Prime Ministers – Trikoupis, Venizelos, Karamanlis – all were known for their conflicts with the monarchy, and some of the most important moments in the country’s history revolved around battles over Republicanism versus monarchism. With the plebiscites of 1973 and ‘74 the Greeks said “no” and got rid of their Kings and Queens.

For number 10, you were probably waiting for us to talk about Greece’s most recent “no”. Instead, let’s think together about this theme of

10. THE CONTRARY GREEKS

Over the sweep of history, Greeks have liked to say “no”. Their “nos” have been variously fierce, defiant, brave, and even confused – but over a remarkably long period of time, at critical historical junctures, Greeks have preferred to say “no”, even when the odds were stacked against them. Indeed, especially when the odds were stacked against them. Perhaps it is this tendency to say NO that has most determined the arc of Greek history. It is certainly what has led to Greece’s bravest and most notorious moments. For the Greeks have said “no” at the least promising of times, at times when to say “no” was a virtual guarantee of defeat. Some of these “nos” have led to victory, and some have led to catastrophe and death. Some have been pointless, and others confused. But all have given the Greeks a hard-earned reputation for bravery and resistance, not to mention for being contrary. And thus “no” has, for the Greeks, become the most positive and proud stance of all – and saying “no” has become a Greek political habit.

Greece is remembered as the most valiant of European nations for resisting against all odds. As Winston Churchill famously declared in the early stages of World War II: “Until now it has been said that the Greeks fight like heroes. Now we shall say: heroes fight like Greeks.” As a scrappy underdog the Greeks have been at their best and bravest. With defeat hanging over them they have been their most victorious.

Paradoxically, it is when they are least with hope that the Greeks have been their most heroic – in saying “no”, regardless of the outcome.

Saying “no” is so important to the Greeks, that a national holiday, October 28th, celebrates it annually – “NO DAY”, “ΟΧΙ Day”, as it called in Greek.

A podcast from ISTORIMA for October 28th.