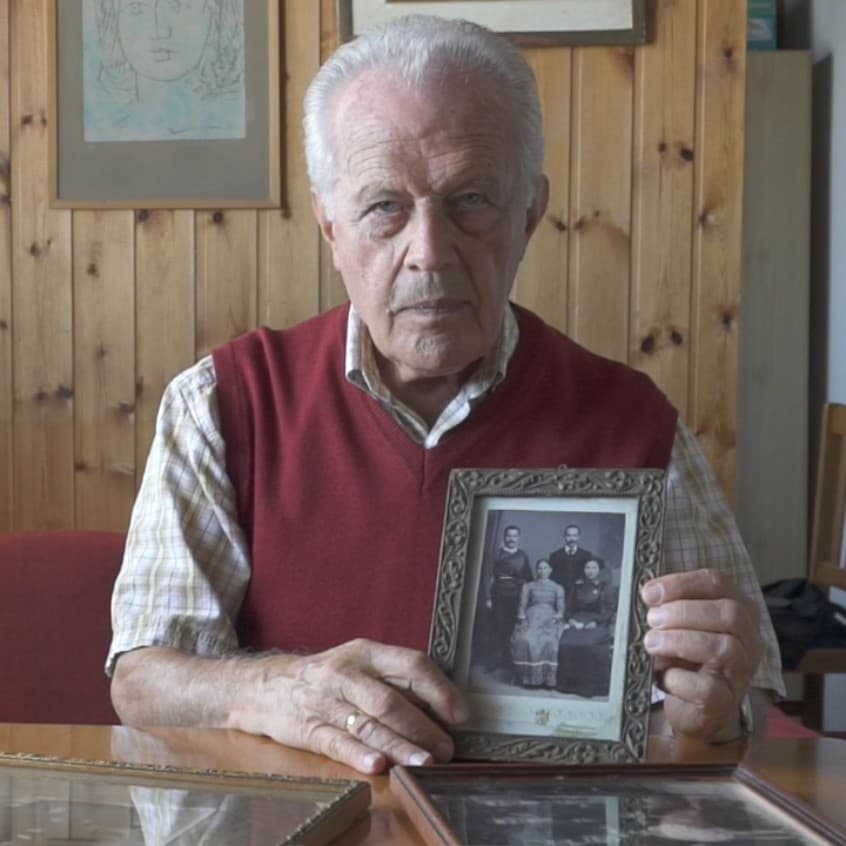

Our village is called Monastiri or Petroulianika. The entire village belonged to the Petroula family. During the German occupation my father, Sotiris Petroulas, was a resistance fighter with the left-wing Greek People's Liberation Army. Then, the Civil War came.

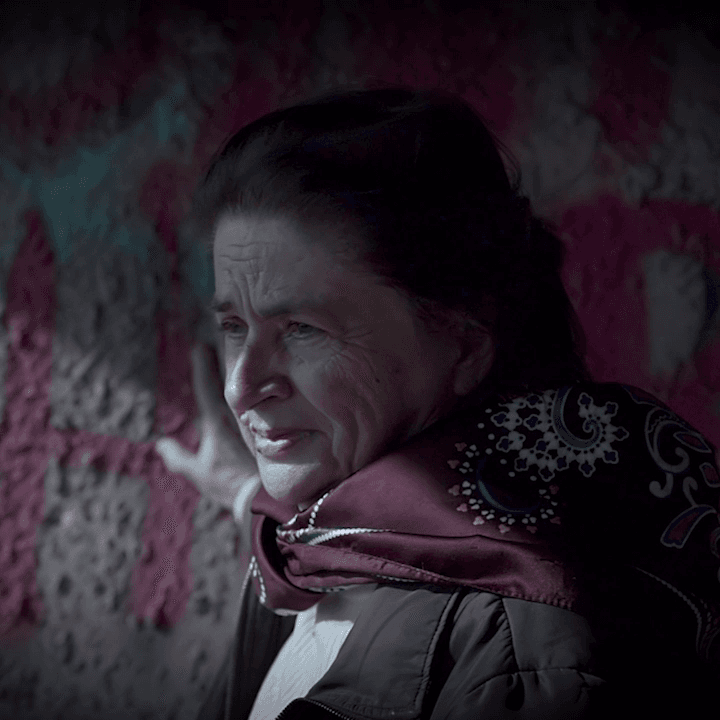

The 20th of January for me was the darkest, the blackest, there is no other, date of my life. It was a Sunday, in 1946, when the Chites, members of the Organization X, a right-wing paramilitary militia, came to our village. I was about three-and-a-half years old at the time. They asked me, because I was sitting in the yard of the house: “Where the hell is your mother?”

I realized it was the Chites, and I went in and told my mother: “Mom, mom, they came, the Chites came!” She picked me up in her arms and tried to close the door. But unfortunately, they broke it down, came in, and pulled my mother outside.

After a while, I saw my entire family, uncles, aunts, cousins, lined up: And across from this line, about ten men, Chites, with guns. One of them in fact had an automatic, and automatic rifle with small iron legs, and that made an impression on me then, because all the other guns were without legs.

My mother was holding me in her arms, and she put me down, because I was three-years old then, and I was hanging on to her skirts, I went where she went. My little hand was holding my mother’s skirt tight, this long brown skirt.

They started killing them, everyone.

My mother, perhaps trying to save me, she threw me aside, she took my hand off her skirt and went up to the front of the entire line and they were shooting her with this gun on legs. They riddled her with bullets.

They all fell down. I was left standing. And I was left standing with my hair tangled up in a bush and I could not move at all. So, one of them came up to me with a gun and put it against my forehead. Not on the side, on the front.

Some were saying: “Kill her!” Others were saying: “No, not the poor thing, let her go...” I was furious. “Poor thing?”, the daughter of Petroulas, “poor thing?” The other one was saying: “She is also Sotiris’ seed!” And I felt such joy, to be Sotiris’ daughter...

He put the gun down and said: “I just can't, goddamn it!” And he let me go.

And I stayed there among the dead for two days and nights.

At some point, my father arrived, with my brother Vassos. But my father and my brother didn’t see me, and I guess I couldn't speak. I saw them, but I couldn’t talk to them.

My one sister however was not dead, she was injured. When they put my injured sister on this ladder, with a gray blanket underneath, and they were carrying her, my father walking behind, he looked old to me. Why would he look old to me? Because he had white hair. He went white instantly when he saw my mother killed, his brother, his daughters, he went white. His hair.

They tried to call the doctor, to get the bullets out, because she was not fatally injured. She had been hit by four bullets. But the doctor, the Chites had told him: “Don’t you dare go, because we will kill you too, we will go up and kill the rest!” So the doctor didn’t go. My sister Kalliopi died of gangrene in the end, twelve years old.

Finally, I remember when they came and buried them, and I wanted to get into the grave to go with my mother. All that however seemed like a game to me, I hadn't realized, I hadn't connected the images that I saw with their meaning. What it was that I was looking at.

I remember my father sitting in a room, there was only a lamp, we had no electric light then, he was giving me bread and oil and I was looking at him and he didn't even want to look at me. He would only tell me: “Eat, eat your bread”. And I remember a tear on my father’s face.

An aunt took me in later. She was the wife of my father’s brother. I didn’t have a good time with her, the woman was dirt poor, and I was always hungry. And where everyone had me used to being loved, to being dressed nicely, being fed, being taken care of, her son would beat me up because I wet myself. With the belt. Was I even aware that I wet myself?

The Chites came and killed her too, it was June ‘48, no '47. Was I already five years old? They killed her, her sister, her son, and her daughter.

The daughter was around fifteen years old, the older one, she was called Potoula. When the Chites came in, they slaughtered her, they butchered Potoula. When I saw her, I lost my mind. They had cut off her lips, they had... I can't describe what it was like.

They killed Petros, her son who would beat me with the belt, he was around fourteen years old, Petros. I may have been afraid of him, but when I saw him killed, I begged him to get up, and I told him: “Look at me, I wet myself, I wet myself! Get up to beat me! Get up! I wet myself...”

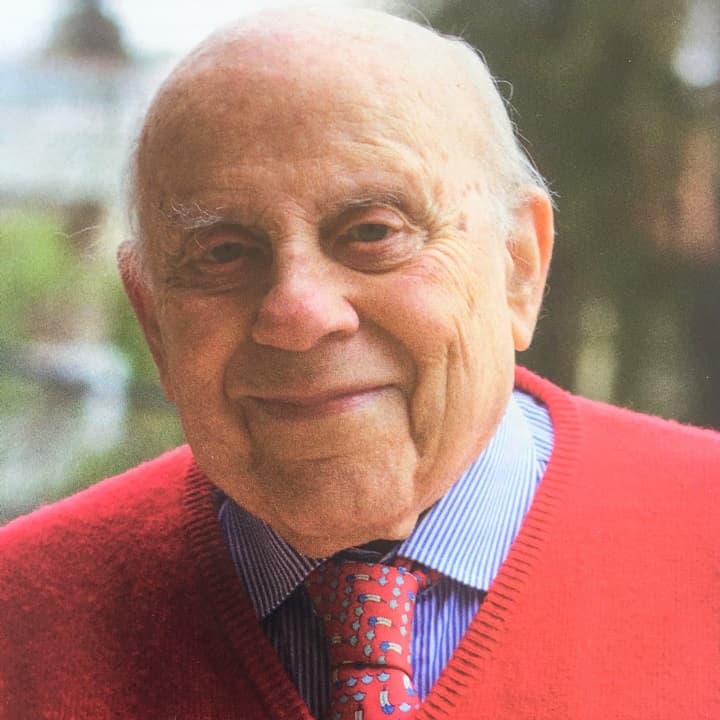

So, my father, after that, went and surrendered himself. Because they had said that anyone from the Greek People's Liberation Army who surrendered their weapons, would get... would not be tried.

When my father went and presented himself at the prison in Sparta, my brother Antonis, my older brother, was also in the Sparta prison. And when he saw my father, he said: “Look at this old man with the beard and the white hair who is almost blind, he looks a lot like my father”. And it was indeed his father, who had not shaved, as the men from Mani used to do, since his brother and wife and children were killed, until he went to the prison of Sparta.

On March 13th, a jeep full of Chites ran over a hand grenade and they thought the guerrillas had put it there, because there was still a Civil War going on. And they went to the prison in Sparta and they wanted to go in, to go in and kill the prisoners. The prison warden tried to stop them, and they killed him. They went into the Sparta prison, killed most of them and they were yelling: “The bearded one! The bearded one!”, meaning my father. And they killed him close to a palm tree.

I don’t remember my father at all, his face. I remember scenes. How he would come in from outside, and as the door opened and the sun was shining - the house was dark - he had an orange in his hand for me. And they tell me that I was the only child he had held in his arms and sung lullabies to.

My middle brother, Vassos, brought me to Piraeus to this lady. He called her a “nice auntie” and said I would stay with her until things got better. I was a child then, all I could imagine was that these “things” were like sacks, sacks, sacks, sacks, which they had to put in order. And I would say: “But I can sleep on the things and be with you, do I have to go to the nice auntie?”

My middle brother, Vassos, was injured in the battle of Kalavryta with the Democratic Army of Greece and they left him at Helmos, believing that they would return to pick him up. But they couldn’t get back there, and the government army found him injured and finished him off, because they wanted him to tell them the number of the guerrillas, how many there were in the Democratic Army.

The years went by, and the nice lady wanted, I don’t know how, she wanted me to believe that she was my real mother. Now, it’s not possible to tell a five-year old child that your mother is not your mother - I am. I pretended to believe it, because I sensed that this lady wanted to believe herself that I was her child. I had a little dog which the Chites killed when they came in the village, his name was Leoutsis. At night when I went to my bed, this dog, in my mind every night, instead of my pillow, for instance, I pretended it was Leoutsis, and I would tell him: “I am Dimitra Petroula, the daughter of Sotiris and Marigoula, I am not the daughter of Artemisia!” - Artemisia was the nice lady’s name. So I wouldn’t forget.

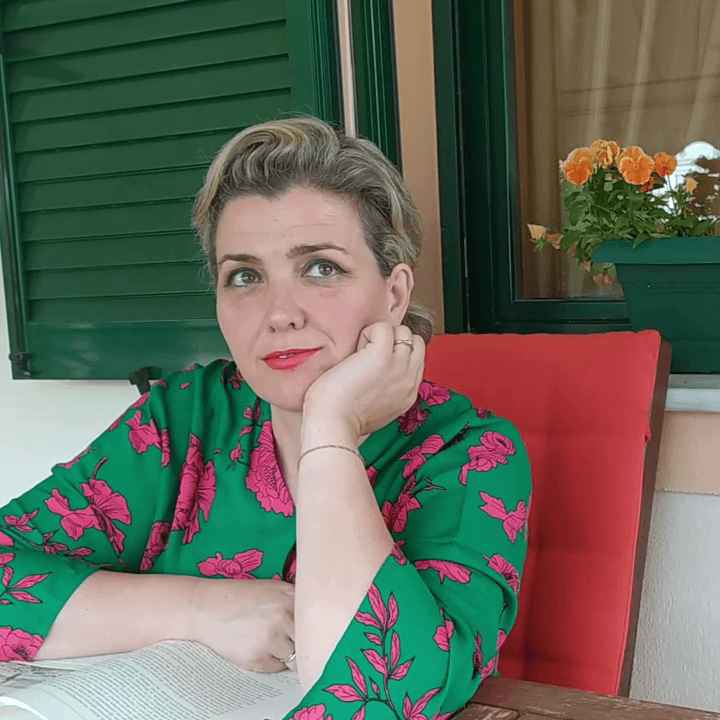

At some point, the lady’s sister came, and I had had some sort of argument, no need to go into the details of it. And she called my father and my mother names. She told me: “Your mother the whore, and your father the criminal!” I told her then: “Don't speak of my mother and my father, wash your mouth with rose water! Just so you know, I will leave”.

Back in September of 1958 we had gone to Corfu, to visit my brother in prison, and I had met a Libyan, we had talked all night, we talked, we talked in English anyway, and sometimes in Italian, and then we exchanged letters. And he had proposed to me.

When the sister of Artemisia said those things about mother and father to me, I wrote to him: “Does the marriage proposal still stand?” He answered: “Yes”. Now, at sixteen, how can you know what love is? I mainly saw it as an opportunity to get away.

And on December 22nd, we got married at Saint Konstantinos church, with a Greek wedding. I didn't want to leave Greece and have them say that the daughter of Petroulas left and was unwed, or whatever, as they say in villages. And in early January, instead of going to school, I went to the airport and we left for Libya.

My husband wasn’t bad, that is, he didn't gamble or drink or... My husband however, according to the reality, the customs and traditions of the Muslims, they have women only to wipe their feet, they are nothing. The women, I tell you, are there to wipe their feet. Well, I didn’t have a good time. He wasn’t a good husband. He was abusive. And I, because everybody beat me up, everybody! Everybody beat me, so when my husband beat me, I thought well, everyone beats me, why shouldn’t my husband beat me? He beat me a lot, a lot of jealousy, a lot. That’s it. I shouldn’t go on.

The children who murdered my mother, who were together with the Chites, seventeen or eighteen years old, are also victims, along with my parents, my mother and my sisters and the others. Why? Because before they had a chance to become people, they were taken by the Chites and they turned them into beasts. Because what would a seventeen-year-old have against my sister, he didn’t even know her, she was eleven, twelve years old? And the other one, fourteen? What could he have against my mother? My aunt? My cousin, who was seventeen years old, seven months pregnant and I saw the baby in her intestines, and I saw the chickens eating my uncle’s brains? What? What? What? They didn’t know us.

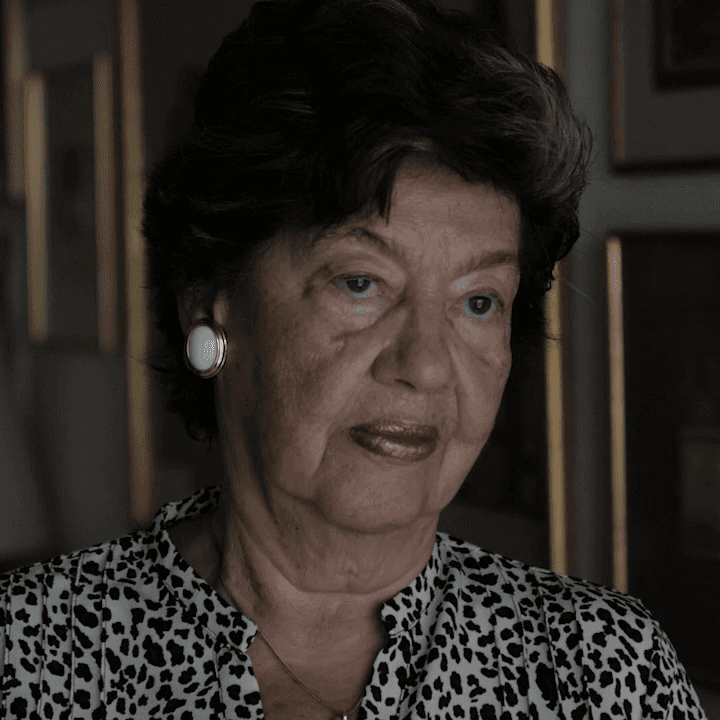

The Civil War, unfortunately, is like that. There is no worse war. Do you understand? That is the whole story. My name is Dimitra Petroula, daughter of Sotiris and Marigoula. I am now nearly eighty. That is my story.